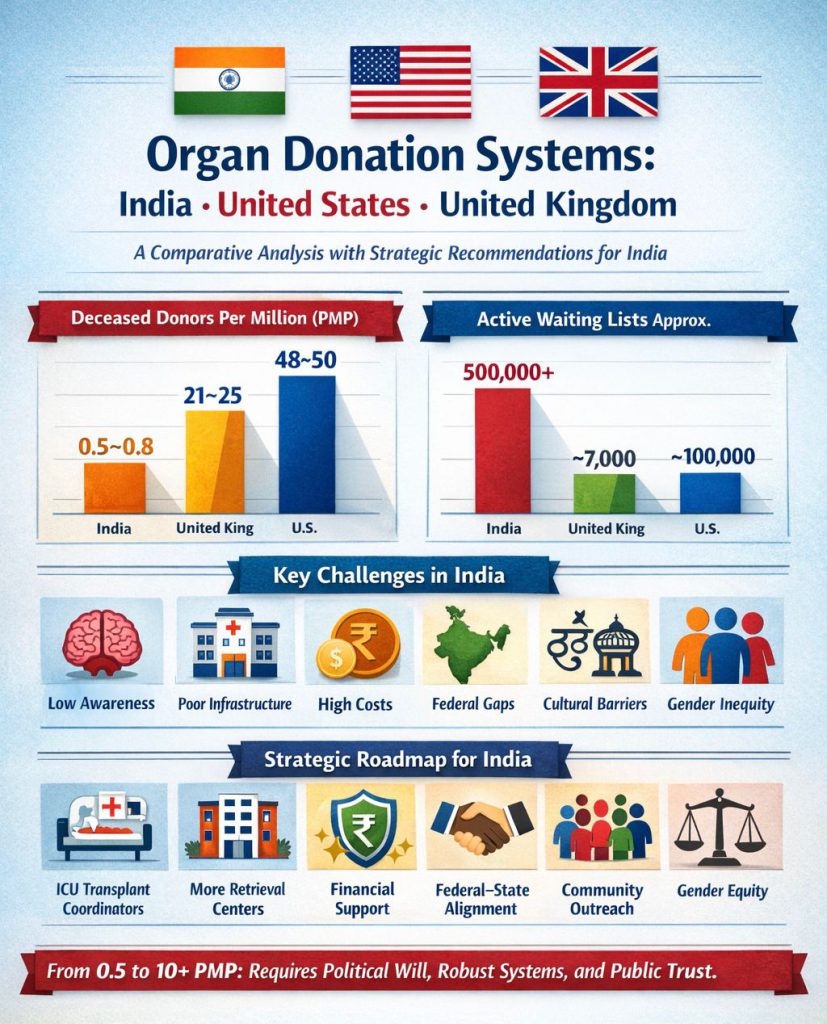

A Comparative Analysis with Strategic Recommendations for India

Rotarian Lal Goel | Founder & Charter President | Rotary Club of Organ Donation International

Organ donation systems worldwide confront a shared challenge: transplant demand vastly exceeds organ availability. Even high-performing systems fall short. The United States achieves approximately 50 deceased donors per million population (PMP) yet meets only 80% of transplant demand—demonstrating that institutional frameworks matter as much as public altruism.

India, the United States, and the United Kingdom represent three distinct governance models. Their contrasting outcomes offer practical lessons, but only if India’s unique challenges remain central to any proposed solutions.

Comparative Overview

Deceased Donor Rates (PMP)

- India: 0.5–0.8

- United Kingdom: 21–25

- United States: 48–50

Approximate Active Waiting Lists

- India: 500,000+

- United Kingdom: 7,000

- United States: 100,000

India’s challenge is fundamentally operational: converting intent into identification, pledges into retrievals, and policy into practice.

India: National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (NOTTO)

Governance Structure

NOTTO operates under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare through the Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act (THOA). The system follows a three-tier architecture: national coordination, Regional Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisations (ROTTOs), and State Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisations (SOTTOs).

Because health is constitutionally a State subject, NOTTO lacks binding authority over State governments. Many SOTTOs exist nominally or function intermittently, often dependent on NGOs or individual advocates rather than systematic institutional support.

Core Functions

- Awareness and Registration: National campaigns, online donor registry, 24×7 helpline

- Capacity Development: Training transplant coordinators and ICU staff

- Allocation and Logistics: Standardised allocation protocols, green corridors for organ transport

- Regulatory Oversight: Preventing commercial exploitation and enforcing THOA provisions

Despite over 480,000 registered pledges, actual deceased donation remains at 0.5–0.8 PMP—revealing a substantial gap between intention and implementation.

Critical Challenges

1. Insufficient Awareness

Brain death remains poorly understood, even among healthcare professionals. Families rarely discuss organ donation before medical crises occur, leaving decisions to be made under extreme emotional distress.

2. Infrastructure Deficits

Only a small fraction of India’s districts have functional organ retrieval centres. Approximately 15–20% of hospitals possess ICU capabilities adequate for deceased donation protocols. Rural and semi-urban areas remain largely excluded from the donation network.

3. Financial Barriers

Transplant procedures are prohibitively expensive for most families. Insurance coverage is inconsistent, government support mechanisms are limited and administratively slow, and long-term immunosuppression costs are rarely covered comprehensively.

4. Limited Federal Authority

Without enforceable oversight of State-level implementation, outcomes depend heavily on local political will—creating wide inter-state disparities. Tamil Nadu consistently achieves over 1.5 PMP, demonstrating what Indian states can accomplish with sustained commitment and effective systems.

5. Cultural and Religious Misconceptions

Persistent myths about bodily integrity, rebirth, and funeral rituals create hesitation. The absence of clear guidance from religious and community leaders reinforces uncertainty.

6. Gender Disparities

Women are over-represented as living donors but under-represented as recipients. Social norms, financial dependence, and differential access to healthcare drive this imbalance.

United States: Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN/UNOS)

The US system operates through a decentralised but accountable framework, with 55 professional Organ Procurement Organisations (OPOs) coordinating donations. The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) manages allocation through advanced digital systems (UNet) with real-time matching capabilities.

Strong performance incentives, transparent public reporting, and consistent federal oversight drive results: approximately 46,000–48,000 transplants annually at 50 PMP. The system demonstrates that professionalisation and accountability—not legislation alone—drive outcomes.

United Kingdom: NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT)

The UK employs a fully centralised national authority with Specialist Nurses for Organ Donation embedded in hospitals. National retrieval teams and unified logistics ensure consistent service delivery. While England operates under a “soft opt-out” consent system, families are always consulted before proceeding.

The UK performs over 4,000 transplants annually at 21–25 PMP, demonstrating that cultural normalisation and bedside expertise can be as effective as legislative frameworks.

Key Insight: Systems Create Donors, Not Laws Alone

Spain achieves approximately 50 PMP with an opt-out system, but its success derives primarily from trained professionals, systematic hospital identification protocols, and robust infrastructure—not the consent framework itself.

Strategic Roadmap for India

Vision

- 5-year target: 2–3 PMP

- 10-year target: 10+ PMP

Priority Actions

1. Professionalise Donor Identification

Require trained transplant coordinators in every ICU-capable hospital. Link brain-death identification audits to hospital licensing and accreditation standards.

2. Expand District-Level Infrastructure

Establish at least one functional organ retrieval centre per revenue district. Strengthen public-sector ICU capabilities rather than relying exclusively on private hospitals.

3. Ensure Financial Protection

Create a uniform national transplant insurance package. Provide comprehensive government support for economically vulnerable recipients, including post-transplant immunosuppression medications.

4. Strengthen Federal-State Coordination

Implement performance-linked funding for States with transparent, publicly reported benchmarks. Establish clear national standards while respecting State autonomy.

5. Sustain Cultural Engagement

Move beyond episodic campaigns to continuous community engagement. Actively involve religious leaders, women’s organisations, and local influencers in normalising donation discussions.

6. Address Gender Inequities

Require mandatory counselling and ethics review for living donations. Implement priority correction mechanisms to ensure equitable access for women recipients.

Conclusion

India’s organ donation challenge is fundamentally systemic. With 0.5–0.8 deceased donors PMP and a waiting list exceeding 500,000, thousands die annually—not from lack of compassion, but from fragmented execution.

The United States demonstrates the power of accountable decentralisation. The United Kingdom shows the impact of centralised expertise and cultural normalisation. India must adapt—not copy—these approaches to its federal structure, economic realities, and cultural context.

The path from 0.8 to 10+ PMP is challenging but achievable. What is required is sustained political commitment, empowered institutional systems, professional staffing, and community trust.

The question is no longer what must be done. It is whether India will choose to implement these solutions—at scale, with urgency, and with consistency.

Thousands of lives depend on that choice.